This is the third part of a new article in the Journal of Biblical and Theological Studies (10.1, April 9, 2025). For the whole article, see: “The Puritan Roots of the American Baptist Movement”.

Spilsbury and the Jacob-Lathrop-Jessey circle of churches baptized people who migrated to America and became members of Baptist churches there. Some New England Puritans became Baptists and returned to England. For example, Hanserd Knollys’ (1599–1691) course seems typical for many Puritan-Baptists.

Murray Tolmie, The Triumph of the Saints: The Separate Churches of London 1616-1649 (Cambridge University Press: 1977), 20.

He began as a Cambridge-educated Church of England minister but felt it necessary to resign after two or three years because of his Puritan principles. He notes that in his youth he “got acquaintance with gracious Christians, then called Puritans.”[1] He became a separatist and then fled to New England to escape the archbishop’s high commission. Apparently, sometime in New Hampshire he became what Cotton Mather (1663-1728) termed a “godly Anabaptist.”[2]

Hanserd Knollys

He returned to London in 1641 where he encouraged Henry Jessey (1603-1660) to become Baptist.[3] Knollys joined the Particular Baptists in 1644, surviving to be a signatory to the 1689 London Baptist Confession. That confession was, essentially, a Baptist version of the Congregational Savoy Declaration (1658) which was, in turn, based on the Westminster Confession of Faith (1646), the classic Puritan confession.

Also subscribing to the 1689 confession was Benjamin Keach (1640 –1704) pastor at Horsleydown. Keach begat Elias Keach in 1666. In 1686 Elias sailed for Philadelphia where he was converted after fraudulently representing himself as a pastor. The younger Keach would plant Lower Dublin Baptist Church (also known as Pennepack Baptist Church) along the same principles of his father. Keach’s Pennsylvania church would spawn several other churches from which the Philadelphia Baptist Association, the oldest in America, would emerge.[4]

News of persecution of Baptists in New England deterred those in old England from following in the footsteps of their Puritan brethren and emigrating. Even when the Clarendon Code (1661–65) was passed – four acts of Parliament designed to discourage the Puritans and other dissenters, in England after the restoration – and Baptists were now persecuted in old England too, still the specter of persecution in New England prevented any “Great Migration” of Particular Baptists there. Only one leading Baptist pastor, the Welsch John Miles (c. 1621–1683), emigrated to New England, settling, wisely, in the Plymouth colony in 1663.[5]

Claiming that persecution proves that Puritans and Baptists were radically different is akin to claiming that the Revolutionary War proves that America did not arise from Britain.

Some suggest that floggings and fines meted out by the Puritan “standing order” to Baptists are evidence of a radically different faith. This is not necessarily so. People with affinities tend to grow up beside one another, and then one or both groups may enforce their distinctives and persecute the minority, which is in many ways similar. Baptists grew up amid Congregationalists because they were so similar.[6] The standing order tried to suppress the distinctives. To claim that persecution proves that the two groups were radically different is akin to claiming that the British campaign in America during the Revolutionary War proves that America did not arise from Britain.

Meanwhile, some of the separatists in exile, mostly in the Netherlands, emigrated to the Plymouth Colony, the “Pilgrims” of Thanksgiving fame. The mainstream Puritans, led by John Winthrop (1587/88 –1649) came to New England, beginning in 1630, to found a “city upon a hill.”[7] When they arrived, they slipped into congregationalism with ease. But it was a momentous decision because it came pregnant with assumptions of ecclesiology that would move Puritans toward becoming Baptists.

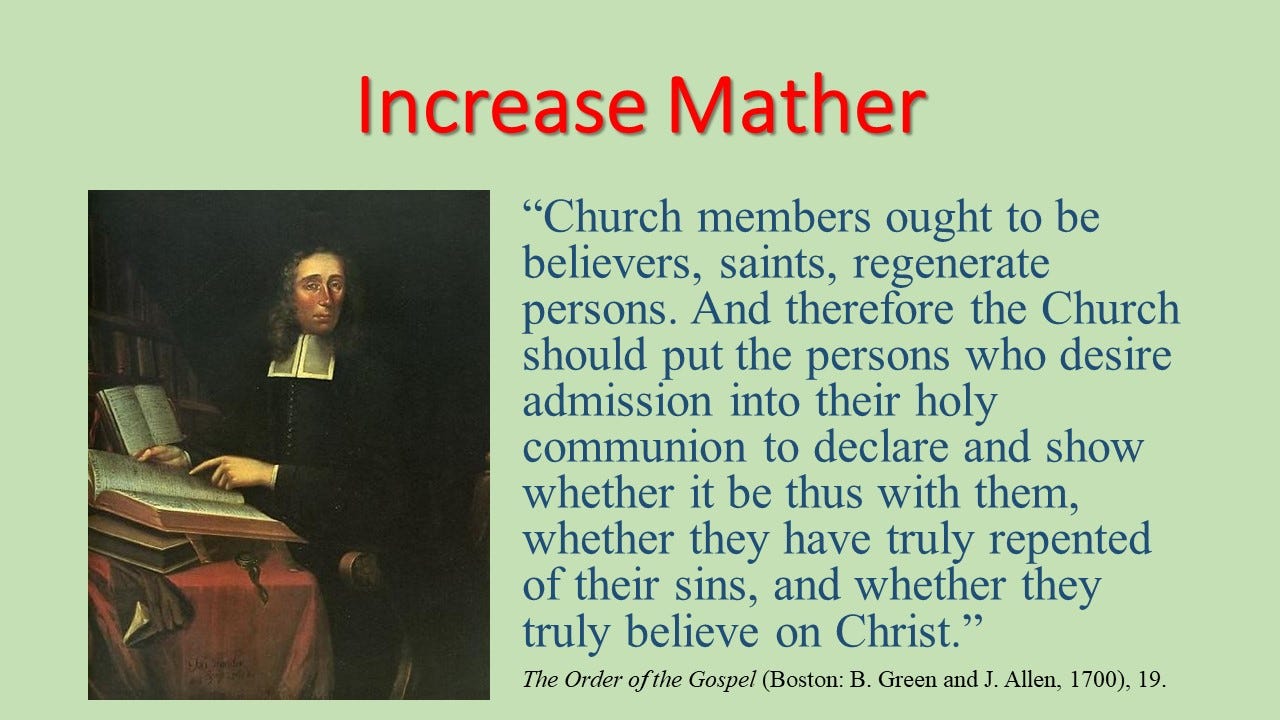

For example, the New England Puritans strengthened congregationalism’s commitment to regenerate church membership.[8] Soon after John Cotton arrived, a revival ensued among the new colonists. The result was that for entry into church membership these Puritans added, to the “Pilgrims” membership requirements of doctrinal subscription and moral living, a public testimony of experienced conversion.[9] Richard Mather wrote defending the practice of “testified regenerate membership” in 1646 and, by 1700, his son, Increase Mather (1639- 1723) was still defending the practice:

Among those “planters of New England” was John Clarke (1609-1676). Clarke, from Suffolk, England, had been educated to be a physician. He arrived in Boston as part of the “Great Migration” in 1637. Apparently, he associated with Anne Hutchison’s antinomians as he was disarmed by the Puritan authorities to prevent an insurrection. By the next year he led a settlement to Aquidneck Island, Rhode Island. There he planted an apparently separatist Puritan church. The next year, Clarke moved to Newport, Rhode Island where he gathered another church. By 1644, under the influence of elder Mark Lucar, associated with Spilsbury’s church in London, Clarke’s church embraced believer’s baptism.[11] The church exists today as United Baptist Church.[12] His church kept close ties to the Baptists in Massachusetts Bay and cultivated Baptist congregations in the other Puritan colonies. In 1649, after a group of church members in Seekonk (then in Plymouth Colony but later in Rehoboth, Massachusetts) came to Baptist convictions and withdrew from their established church, Clarke arrived to provide pastoral care.[13]

John Clark

Two years later, in 1651, Clarke and Obadiah Holmes, originally from the Seekonk church, arrived in Lynn, Massachusetts, to fellowship with Walter Witter, an elderly man of Baptist principles. Their meeting was interrupted by two constables who compelled Clarke and his associates to attend a Puritan Sabbath service. They protested by refusing to remove their hats. They were sent to trial in Boston where they were sentenced with a heavy fine or to be “well whipt.” Friends of Clarke paid the fine for him but the defiant Obadiah Holmes refused to pay and, so, on September 5, 1651 was given thirty lashes with a three-corded whip leaving him permanently scarred.[14] Some witnesses to the whipping were moved by it to embrace Baptist principles. One such witness was Henry Dunster (1609 –1659).[15]

“Soli visilibiter fideles sunt baptizandi” — Henry Dunster

Dunster was the first president of Harvard College, an esteemed founder of the standing order. But sometime after Holmes’ lashing, he reasoned, in good Reformed-style, “all instituted Gospel Worship hath some express word of Scripture. But paedobaptism hath none.”[16] The fundamental issue, however, was, again, the identity of the church as the gathering of the regenerate. “Soli visilibiter fideles sunt baptizandi” (“Only the visible believers are to be baptized.”) Since he could not see that infants were believers, they were not eligible for baptism.[17] Unlike some Baptists of the first two generations, he was not unnecessarily inflammatory; he was irenic, and so was not excommunicated for his Baptist beliefs from his Puritan church.

Baptists were “among the planters of New England from the beginning, and have been welcome to the communion of our churches…”. — Cotton Mather

In Boston itself, the First Baptist Church was gathered in 1663 and led by Thomas Gould, meeting in homes until they were able to build their first “meeting house” (the Puritan term) in 1678.[18] Gould had been inspired by Dunster but, unlike Dunster, was unwilling to withdraw from Massachusetts, choosing rather to go to prison.[19] He was summoned to court in September 1665 to account for his new church. He presented to the court the Baptist church’s statement of faith, which, in major issues, like the Trinity, Lordship of Christ, and authority of scripture, reflected Puritan orthodoxy.[20] The church grew from its original nine charter members, after the Restoration in England required the loosening of the Puritan yoke in New England, to eighty members fifteen years later. This suggests that quietly dissenting Baptists inhabited many of the Puritan churches.[21] Cotton Mather, the third generation “Lord’s remembrancer,” claimed that Baptists were “among the planters of New England from the beginning, and have been welcome to the communion of our churches, which they have enjoyed, reserving their particular opinion unto themselves.”[22]

John B. Carpenter (Ph.D, ThM, MDiv) is pastor of Covenant Reformed Baptist Church and author of Seven Pillars of a Biblical Church.

[1] Hanserd Knollys, The Life and Death of That Old Disciple of Jesus Christ and Eminent Minister of the Gospel Mr. Hanserd Knollys (London: John Harris, 1692), 4.

[2] Cotton Mather, Magnalia Christi Americana: Or the Ecclesiastical History of New England, III (Hartford, Cn: Silas Andrus, 1820), 221.

[3] Crosby, The History of the English Baptists, 311, 336.

[4] Thomas Kidd and Barry Hankin, Baptists in America: A History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 26. Pennepack Baptist Church, https://www.pennepackbaptist.org/history.html, accessed March 6, 2022.

[5] McLaughlin, 76.

[6] See John B. Carpenter, “Baptist Polity Inherited from Congregationalism,” Journal of Baptist Theology and Ministry 20.2 (Fall 2023), 153-172, https://www.nobts.edu/baptist-center-theology/journals/journals/jbtm20b.pdf.

[7] John Winthrop, A Modell of Christian Charity (1630).

[8] See Carpenter, “Baptist Polity Inherited from Congregationalism,” JBTM 20.2, 154-158.

[9] Richard Mather, Church-Government and Church-Covenant Discussed (London: R. O. and G. D., 1643), 23.

[10] Increase Mather, The Order of the Gospel (Boston: B. Green and J. Allen, 1700), 19.

[11] Chute, Finn & Haykin, The Baptist Story, 32.

[12] United Baptist Church, history, https://unitedbaptistnewport.com/history/, accessed March 14, 2022.

[13] Sydney V. James; Bozeman, Theodore Dwight (ed.). John Clarke and His Legacies: Religion and Law in Colonial Rhode Island, 1638–1750, (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1999), 43.

[14] Thomas Williams Bicknell, The Story of Dr. John Clarke, (Little Rock, Arkansas: The Baptist Standard Bearer, Inc., 2005), 48.

[15] Louis Franklin Asher, John Clarke (1609–1676): Pioneer in American Medicine, Democratic Ideals, and Champion of Religious Liberty (Pittsburgh, PA: Dorrance Publishing Company, 1997). Samuel Eliot Morison, Builders of the Bay Colony (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1930), 183–216.

[16] Jeremiah Chaplin, Life of Henry Dunster (Boston: James R. Osgood and Company, 1872), 112.

[17] William McLaughlin, “The Rise of Antipedobaptists in New England, 1630-1655,” Baptists in the Balance: The Tension Between Freedom and Responsibility, edited by Everett C. Goodwin (Valley Forge, PA: Judson Press, 1997), 90.

[18] First Baptist Church of Boston, https://www.firstbaptistboston.org/history.html, accessed March 4, 2022.

[19] Stanley Grenz, Isaac Backus — Puritan and Baptist: His Place in History, His Thought, and Their Implications for Modern Baptist Theology (Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 1983), 46. Alternately the name is spelled Goold, in Thomas S. Kidd and Barry N. Hankins, Baptists in America: A History (Oxford University Press, 2015).

[20] Kidd and Hankins, Baptists in America 16.

[21] McLaughlin, 79.

[22] The Great Works of Christ in America, 2, 532-33.