New England's Puritan Century: Generation III

Fides et Historia, vol. XXXV, no. 1: 41-58 (part 3)

“It’s part of the generation work of every Christian, to do his utmost that the Lord’s Name and Honor may be held up to the succeeding generation.” -- Eleazer Mather[1]

“I speak now to the generation coming on upon the stage, if you or a considerable number of you do not take care to be right spirited for God, that you may duly manage his work and carry it on, and serve the God of your fathers with a perfect heart and willing mind, you will be like to destroy and lay this pleasant land desolate.” – William Adams[2]

After the Glorious Revolution, King William issued Massachusetts a new charter in which the main pillar of religious control was permanently removed. The franchise was granted based on property rather than church membership. Those hoping that Increase Mather could bring back the original charter were disappointed. The constitutional basis for Massachusetts’ era of de facto independence was dissolved. The Puritan commonwealth was hereafter politically connected to a larger body politic. The third generation of New England Puritans would have to learn to get along in a world not of their making. But “the oppositional mentality” – the jihad – had been awakened, and it would not die down easily. The tendency of this time, so notes Samuel E. Morison, was “to tighten up,” and insist on undiluted Puritanism.[3]

This aroused “oppositional mentality” may be behind two domestic New England controversies, one very well known. Most Americans, if they have any knowledge at all of this period, think of the Salem witchcraft trials. Kenneth A. Lockridge and Paul Boyer, and Stephen Nissenbaum portray the Salem trials as a cultural “Battle of the Bulge,” a desperate Puritan counter-attack, especially by the Puritan hinterland, against the forces of cosmopolitanism. Lockridge believes that in the trials, the citizens of Salem Village were taking a stand for an intensely localistic version of Puritanism. They were reacting against “corruptions that smacked not simply of a different life-style but also of a higher authority which would doom their life-style to extinction.”[4] The Puritans would not necessarily differ with this interpretation.

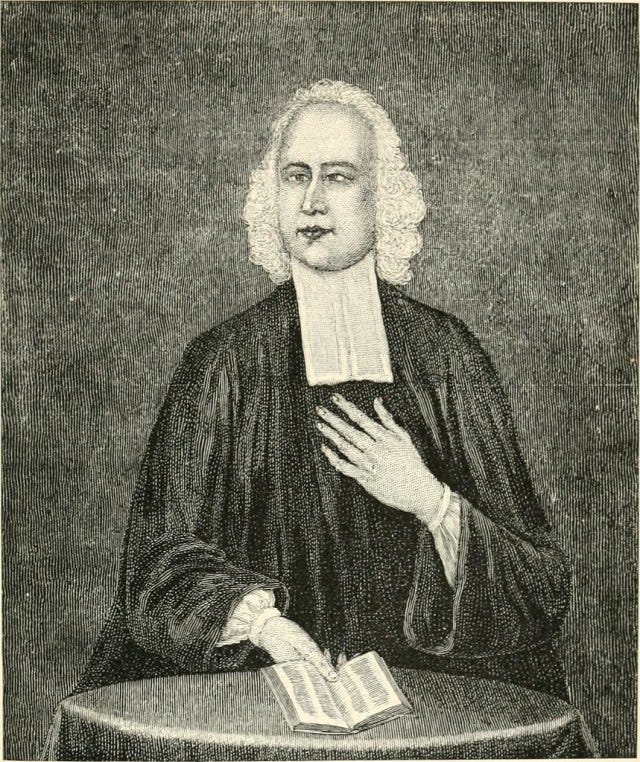

Cotton Mather himself stated that the reason for the outbreak of witchcraft was that Puritanism so opposed such things. “Where will Satan show the most malice but where he is hated and hated most.”[5] While the modern interpretation is that they were nothing more than mass hysteria combined with slack judicial practices, in fact it is reasonable to suppose that in a culture in which people believed that witchcraft was a real avenue to supernatural power, that some people would try it, especially those, like West Indian slaves, who were on the fringes of Puritan society.[6] When African and even ancient Anglo-Saxon folklore came into contact with Puritan scruples, the result was deadly.

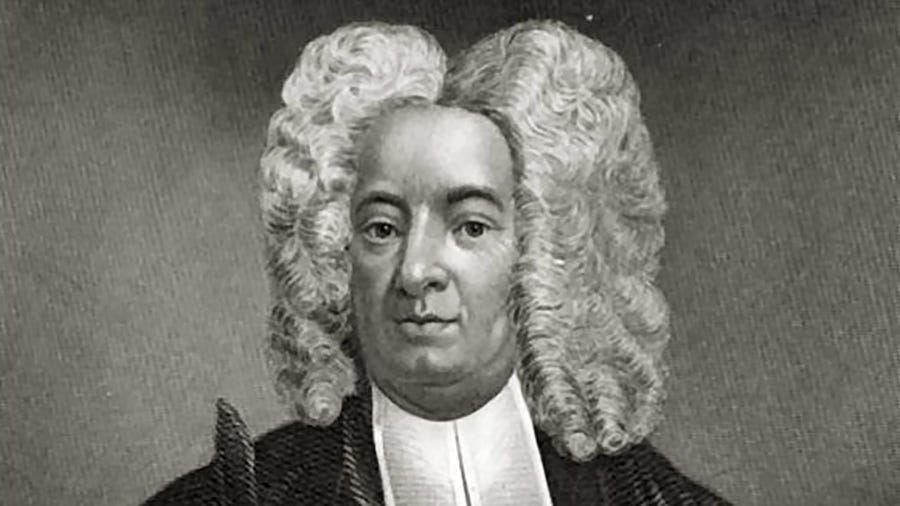

Increase Mather’s debate with Solomon Stoddard on giving liberal access to the Lord’s Supper is another controversy that may never have been fired to such heat if it was not for the spirit of jihad in the air. In the wilderness, Stoddard (1643-1729) broke with some aspects of the New England way but certainly not with Puritanism itself.[7] Stoddard took the primitivist dimension of Puritanism one step further back into the Old Testament. “If one wished the restoration of the ‘pure’ church,” observes Paul R. Lucas, “one looked first at the polity of God’s church among the ancient lsraelites.”[8] Stoddard, unlike the New England mainstream, interpreted all of New England to be equivalent to Israel, rather than just the elect in New England.[9] Stoddard’s misstep, though, should be seen in context. In the absence of significant religious competition, he could afford to herd everyone into the church to put them all in the way of grace.

In addition, Stoddard had a thought-out theological rationale. “The inward actings of grace are invisible to others.” Someone may have grace and not (yet) show it, while another may be counterfeiting “the visible actings of grace.” It is, then, too difficult to discern the sheep from the goats.[10] Stoddard questioned the ability of Christians to accurately separate the sheep from the goats (in his 1687 tract The Safety of Appearing at the Day of Judgment in the Righteousness of Christ) and therefore advocated giving communion to all who were orthodox theologically and lead scandal-free lives. His open communion was not as radical as some make it out to be. Boston’s Third Church, Charlestown, Cambridge, and Watertown, by down-playing the “test of relation,” each had widened the circle of those eligible for communion by the end of the seventeenth century.[11] Stoddard certainly did not regard all New Englanders as regenerate saints; he even had his suspicions about some of his fellow clergy. Stoddard’s move, though at variance with the letter of New England practice, was in keeping with its evangelistic spirit.[12] Stoddard argued that he was no innovator, that he was in keeping with “the pillars of the churches of New England.”[13]

At first, the formation of the Brattle Street Church (1699) appeared to be a significant defection from supposed Puritan exclusivity to English latitudinarianism. Among the founders of Brattle Street, “a group of modernists,” two were grandsons of former governors of Massachusetts, and around them “coalesced a larger group, most of them men of business.”[14] They called Benjamin Colman, a son of Massachusetts who had gone to England; he received Presbyterian ordination before returning to take over Brattle Street. Upon his return, Colman issued a manifesto that implicitly challenged the Cambridge Platform. Colman turned out to be no more a rationalist and latitudinarian than Stoddard, who only opened communion so he could have fuller congregations for his hell-fire, conversionist sermons. Colman was committed to a church of visible saints, too, even if he thought the New England Way’s tradition of discerning the saints was no longer useful.[15]

Colman lived to see and support the Great Awakening. Far from being the “outstanding liberal” Edwin Gaustad claims him to be, Colman “remained staunchly Calvinist in theology and a friend to the new evangelical revivals.” George Whitefield himself would remark favorably on Colman’s gospel preaching (and vice versa).[16] Meanwhile, Samuel Willard (1640-1707), acting president of Harvard after Increase Mather, was just as orthodox as the Mathers and so could mitigate the latitudinarian influence.[17] Eventually, even the Mathers made peace with both Stoddard and Colman.

A more positive fruit of the jihad, the “oppositional mentality,” was the rise of voluntarism. After the new charter was issued in 1691, the crown-appointed governors were not nearly as active in support of the Puritan “standing order” as the elected governors of the original charter had been. Rather than having become dependent on government protection, Puritan vibrancy showed in the sudden sprouting of voluntary associations and spontaneous movements. In central to western Massachusetts, Stoddard’s Hampshire Association was an attempt to erect an organization of churches for mutual oversight in place of the government’s lost role. Back in the east, both Cotton Mather and Samuel Danforth (1666- 1727) lifted a page from the moral reform movements in England that briefly sprouted during Queen Anne’s reign. They both formed societies to combat vice.

Cotton Mather, starting in 1702, gathered young men to help the Boston authorities enforce moral legislation. His efforts produced little since by 1713 the societies had died and could not be resuscitated. Youth remained, however, a focus of the voluntaristic efforts to rekindle the Puritan fire. Samuel Danforth had more success, perhaps because his groups were more explicitly religious. He led, in Taunton, Massachusetts, the organization of societies for prayer, encouraging family worship and, like Cotton Mather’s groups, self-disciplining of young men. A revival ensued in Taunton in 1705, which was celebrated, in Puritan style, by a covenant renewal service.[18] Increase Mather had championed such services during King Philip’s War as a mass expression of repentance. Amid revival, they turned back to this fading Puritan practice.

Sociologist Adam Seligman sees in these reform societies the Matherian counterpart to Solomon Stoddard’s bringing the world into the Church; Mather and Danforth brought the Church into the world. These developments are fruit from the same tree: Puritanism was finding new forms of institutionalization.[19] This would only have happened if Puritanism was still a living movement even in the third generation.

A Puritan catholicity

New England was a place where “the names Congregational, Presbyterian, Episcopalian, or [Baptist] are swallowed up in that of Christian.” — Cotton Mather

Each of the first three New England Puritan generations demonstrated their yearning for Christian unity around a Reformation core, despite the established congregationalism. Of the first generation, “inclusivistic” John Eliot published The Communion of Churches in 1665. In it, he proposed an organizational compromise between congregational and presbyterian forms. Eliot sought to justify the role of councils of gathered churches.[20] Increase Mather’s “United Brethren” sparked correspondence back and forth between like-minded ministers on both sides of the Atlantic. Cotton Mather celebrated the “Blessed Union” with another publication, proclaiming on its title page, “A most happy union has been lately made between those two eminent parties in England.”[21] He insisted that New England was a place where “the names Congregational, Presbyterian, Episcopalian, or Antipaedobaptist, are swallowed up in that of Christian.”[22] He even planned a grand ministerial association with a standing council to advance the ecumenical spirit but it foundered on congregational independence.[23] New England’s original errand may have changed, somewhat, but for Cotton Mather the new identity had not changed into something less but into something more. England may not be converted en masse but there was still hope for a union of conformists and non-conformists on a Calvinist basis.[24] Stoddard, Danforth, Colman, and the Mathers did not act like Puritanism was a wilting movement.

Declension there may have been in the hearts of the sons and daughters of the founders of the City upon a Hill. But the myth of disintegrating Puritanism with a “liberal” Colman in Boston, a rebel Stoddard in the wilderness, and incipient Arminianism seen in the “moralism” of third-generation Puritans (even Cotton Mather) simply holds no water.[25] Cotton Mather came to believe that even by the 1720s New England ministers were nearly unanimous in holding onto Puritan orthodoxy. He (in 1726) reported that New England Puritans “adhere to the confession of faith, published by the assembly of divines at Westminster. … I cannot learn that among all the pastors of two hundred churches, there is one Arminian.”[26]

Peace With the Baptists

Peace was also made with the Baptists and kept with the Huguenots. Although Increase Mather, like his contemporary Stoddard, had called for more suppression of the Baptists, he also acknowledged the Baptists as legitimate in practice (by inquiring whether the local Baptist church had any objection to John Farnum, who was requesting the right to return to communion at the North Church).[27] His son Cotton preached a sermon at the ordination of a Baptist minister. Cotton Mather was stretching toward the evangelical unity that George Whitefield would later champion.

There was diversity within late New England Puritanism created by Benjamin Colman, Solomon Stoddard, and others. That diversity demonstrated not that Puritanism was unraveling but that in a new environment, the movement could adjust in a variety of ways while maintaining an essential unity. The parochialism of New England Congregationalism was indeed being challenged, but the challenges were on a Puritan basis. A new Puritan catholicity was developing, which was preparing Puritanism for dispersal. Thus, despite the howls of some of the Congregational mainstream, like the young Increase Mather, Puritanism, exhibited in its first century in the New World it had both a firm foundation and a variety of facades on that one foundation. Puritanism had managed nearly a century of stability in the City upon a Hill. It was poised on the launching pad of globalization.

The story of the first three generations of the “City upon a Hill” is not primarily about declension, at least not externally. Virginia D. Anderson notes that of all the early English colonies, only in New England “did the framework of social and cultural institutions created by the first generation of settlers prove remarkably durable.”[28] Indeed, given the pressures they were under from London and the natural centrifugal forces of human society, they managed to hold together to a remarkable degree. Hence, the Puritanism’s ideational culture dominated New England for over a century; for most of the first two generations, that dominance was complete: economic, political, and cultural. But even by the end of the third generation, it was still Puritanism that ruled the culture. Since throughout this period New England was relatively homogeneous, this vibrant Puritan church had the opportunity to shape the common mind from basic presuppositions up.

Insofar as a given system of ideas has existed for a long time in a society at strategic points,

it is a reasonable hypothesis that it exerts a steady influence in the direction of canalizing attitudes in such a way that they will become, in terms of such a system, meaningful. This is the more true, the more the society in question is one characterized by the persistence of aggregates, by strength of “belief.”[29]

So that ideational system of ideas, known as Puritanism, brought that society about and guided it at strategic points, apparently “canalizing attitudes” in a way that they became meaningful and ingrained. Because Puritanism was such an overwhelmingly ideational movement and because it remained vigorous and stable throughout New England’s first century, its strong beliefs made it especially potent in shaping New England society and presumably the new nation in which New England was eventually so influential.

John B. Carpenter (Ph.D, ThM, MDiv) is pastor of Covenant Reformed Baptist Church and author of Seven Pillars of a Biblical Church.

[1] E. Mather,” A Serious Exhortation,” 14.

[2] William Adams, The Necessity of the Pouring out of t/1e Spirit (Boston: John Foster, 1679), 41.

[3] S. E. Morison, Three Centuries of Harvard, 1636-1936 (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 1936), 46.

[4] Kenneth A. Lockridge, Settlement and Unsettlement in Early America: The Crisis of Political Legitimacy Before the Revolution (London: Cambridge University Press, 1981), 39. See also Paul Boyer and Stephen Nissenbaum, Salem Possessed: The Social Origins of Witchcraft (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1974).

[5] Cotton Mather, The Wonders of the Invisible World (London: John Dunton, 1693), 5.

[6] Francis J. Bremer, The Puritan Experiment: New England Society from Bradford to Edwards (Hanover, N. H.: University Press of New England, 1976), 183.

[7] Stoddard argued his case in Solomon Stoddard, An Appeal to the Learned (Boston: B. Green, 1709).

[8] Paul R. Lucas, “‘An Appeal to the Learned’: The Mind of Solomon Stoddard,” William and Mary Quarterly 30 (April 1973), 262.

[9] For example, An Appeal to the Learned, 91.

[10] Solomon Stoddard, The Tryal of Assurance (Boston: B. Green and J. Allen, 1698), 13, 19.

[11] David Hall, The Faithful Shepherd: A History of the New England Ministry in the Seventeenth Century (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1972), 205.

[12] Increase Mather insisted, in opposition to Stoddard’s innovations, that “visible saints are the matter of a particular church.” The Order of the Gospel (Boston: B. Green and J. Allen, 1700), 16.

[13] Stoddard, An Appeal to the Learned, 92.

[14] D. Hall, The Faithful Shepherd, 292-93.

[15] Benjamin Colman, Gospel Order Revived (n.p.: 1700), 2.

[16] Edwin Gaustad, The Great Awakening in New England (New York: Harper, 1957), 52. S. Stout, The Divine Dramatist: George Whitefield and the Rise of Modern Evangelicalism (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1991), 117. Colman encouraged Jonathan Edwards to publish A Faithful Narrative of the Surprising Work of Cod, invited Whitefield to Boston and had him preach at Brattle Street his first Sunday, and in a letter (15 May 1742) called the revival Whitefield fanned into flame “a great and glorious work of God” even while criticizing some of its excesses. Charles Chauncy, The State of Religion in New England Since the Reverend Mr. George Whitefield’s Arrival There (Edinburgh: Robert Foulis, 1742), 42.

[17] James W. Jones, The Shattered Synthesis: New England Puritanism Before the Great Awakening (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1973), 55.

[18] Michael J. Crawford, Seasons of Grace. Colonial New England’s Revival Tradition in Its British Context (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 44-47, 181.

[19] Adam Seligman, “Inner-worldly individualism and the institutionalization of Puritanism in late seventeenth-century New England,” British Journal of Sociology 41: 537-53.

[20] See Eliot’s Communion of Churches.

[21] Cotton Mather, Blessed Unions (Boston: B. Green, 1692), cover.

[22] C. Mather, The Wonders of the Invisible World, 5.

[23] Robert Middlekauff, The Mn/hers: Three Generations of Puritan Intellectuals, 1596-1728 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1971), 224.

[24] C. Mather, Eleutherin, 118-35.

[25] For example, see Cotton Mather’s Eleutheria.

[26] According to Conrad Wright, The Beginnings of Unitarianism in America (Hamden, Conn.: Archon Books, 1955), 9.

[27] Foster, The Long Argument, 199.

[28] Anderson, New England’s Generation, 1. David Hall notes the “remarkable continuity” of the first three generations of ministry in New England (The Faithful Shepherd, 270.)

[29] Talcott Parsons, The Structure of Social Action (New York: Free Press, 1937), 537.