New England's Puritan Century: Generation II

Fides et Historia, vol. XXXV, no. 1: 41-58 (part 2)

My father, when he was leaving this the world, did commend it as his dying council to me, that I should endeavor the good of the rising generation in this country, especially that they might be brought under the government of Christ in his Church. -- Increase Mather[1]

Increase Mather (1639-1723)

Increase Mather stands as the quintessential Puritan over all three generations. By birth, he belongs to the second generation, but his experiences in England gave him a taste of the first, and his longevity allowed him to bury many of the ministers of the third. Although born in New England, he finished his education in Ireland and started his ministry in England, where he had expected to live for the rest of his life. When the enforced conformity of the Restoration came to Guernsey, England, where he was a chaplain, he refused to conform. He experienced the fate of his father, who had been put out by the purges of Archbishop Laud. He underwent the same trials as the first generation of immigrants to New England, and it showed when he returned home to debate over the Halfway covenant. He opposed the innovation at first. However, he eventually came to adopt it and even defended the 1662 Synod as quite in the spirit of the Puritan founders in a 1673 treatise entitled The First Principles of New England. Increase called for diligence in preserving New England as a Congregational homeland. His calls for persecution “evoke a vision of an American Israel in which society and congregations were one.”[2] That, of course, is precisely the original Puritan vision. When in Britain, though, during his sojourn to petition the king for a new charter for Massachusetts, he was key to the formation of the “United Brethren,” a short-lived alliance of Congregationalists, Presbyterians, and other dissenters. Puritanism was never defined exclusively as congregationalism. Even Increase understood, after the Glorious Revolution, that the congregational exclusivism of New England’s first generation, though it may have served its time, was over. Like his father, he saw that new times called for new measures.

A political earthquake in England was a seismic event for the formation of New England in the second generation: the Restoration. During the first generation, Massachusetts could behave like an autonomous nation. In 1655, the General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony banned the importation of malt, wheat, barley, beef, meal, and flour (“the principal commodities of this country”), even from the mother country.[3] This made perfect sense in mercantilist economic theory – if Massachusetts was an independent state. During England’s Commonwealth, Massachusetts was a de facto independent state. Massachusetts flew its own flag; it eliminated the king’s name from the oath of allegiance; it issued land without recognizing the king’s right to it; it banned judicial appeals to the Privy Council. Soon, Charles II would begin to reel them back in.[4].

The Halfway Covenant

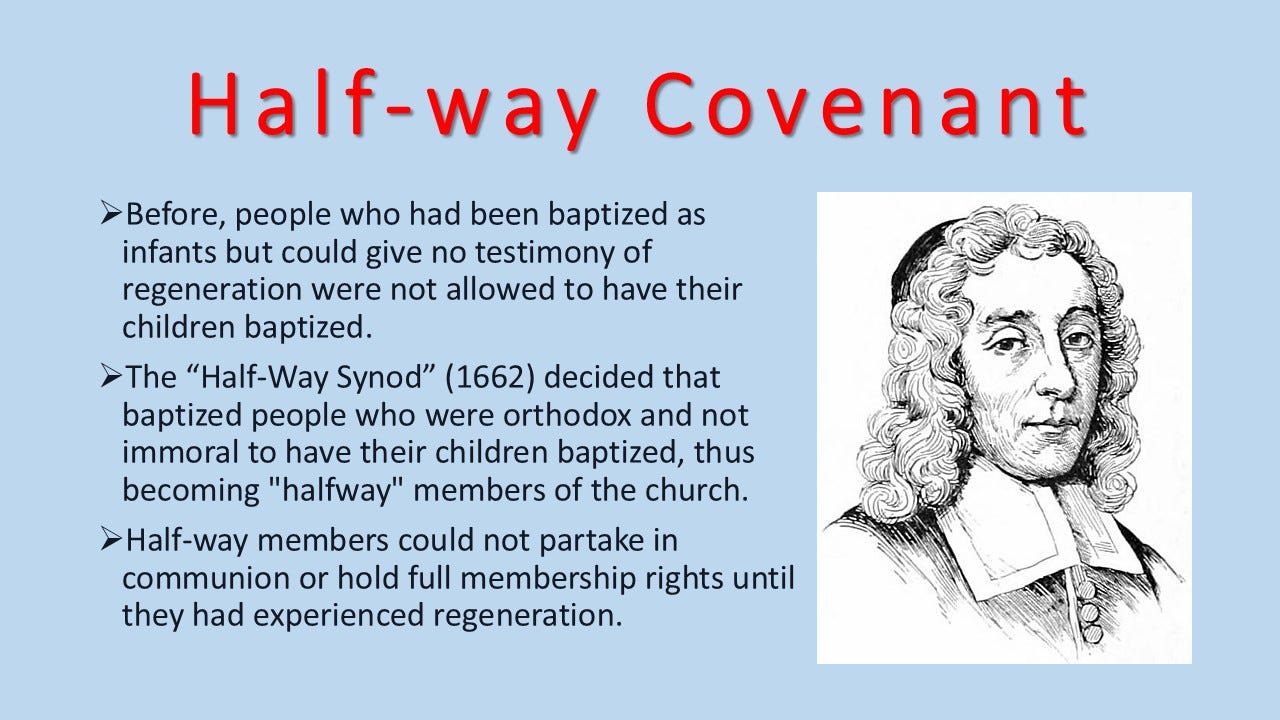

The “Halfway Covenant” is the example par excellence of the Puritan ability to adapt their ideals to new realities. The crisis that instigated the Halfway Covenant was built into the original polity. Only church members were supposed to receive the ordinances of communion and baptism. Puritan theology taught that the covenant which God had made with the elect included their children (at least until they could “own the covenant” for themselves). Hence, the infant children of church members could be baptized. In the original polity, though, when such children grew up without experiencing grace for themselves, they could not be admitted as church members. When they had children, those children-grandchildren of the visible saints-were not even eligible for baptism.

Hence, by the end of the first generation, increasing numbers of New Englanders were unbaptized. The Halfway Synod of 1661 decided that baptized children of church members who were orthodox and were not living scandalously could have their children baptized. The “Halfway Covenant” marked the emergence of New England Puritanism’s sense of responsibility to the whole world. It was then, around 1660, that the “real world” returned to New England “with a vengeance.”[5]

The Halfway Covenant allowed the Puritan church to bring the unregenerate under its ministry without completely dissolving the line between the world and the church.

The widespread adoption of the Halfway Covenant sprang from the Puritan sense of pastoral responsibility for the whole world. The strong party of dissent from the innovation, first from young Increase Mather and about a century later from the New Divinity, sprang from the Puritan commitment to a spotless “Bride of Christ.” The Halfway Covenant was a compromise between the two impulses. The Halfway Covenant provided the perfect institutional compromise between the world and the Church. “Any attempt to square the circle of Puritan religious injunctions demanded: Augustinian dualism on the one hand, and the making of the world one immense monastery on the other.”[6] The Halfway Covenant was a sign of the evangelistic impulse that was to make Puritanism so vibrant. The Halfway Covenant was the Puritan answer to the problem of social diversity. Because society includes everyone, including the unregenerate, a way must be found to preserve the social role of the church. The Halfway Covenant allowed the Puritan church to bring the unregenerate under its ministry without completely dissolving the line between the world and the church.

Anglican businessmen and officials started to increasingly settle in Boston. They reminded Puritans of what set them apart from mainstream English culture. These Tory merchants tempted New England with compromises that had been easy to avoid in the “rarefied atmosphere of the first thirty years of settlement.”[7] But Puritan convictions were not so easily washed away. Puritanism had been able to lay a solid foundation in the first generation. Thus, when the convictions were challenged, they did not evaporate under the hot sun of Cavalier Britain. So, the 1670s were the high point of New England Puritanism because “self-awareness was most fully articulated and before the social, political, and intellectual forces that would erode Puritanism had taken effect.”[8]

This sense of Puritan self-awareness had some political implications. In 1678 the Massachusetts General Court boldly (and probably foolishly) stated: “the laws of England are bounded within the four seas and do not reach America.” As for the tariff, because New England was “not represented in Parliament, so we have not looked at ourselves to be impeded in our trade by them.”[9] Tory Anglicans in New England served to unify Puritans in opposition, in the short term, more than to create converts to the Royalists. Edward Randolph (1632-1703), an Anglican and “staunch royalist,” was appointed by the Lords of Trade to inspect the adherence of the Massachusetts government to the Navigation Acts and the 1673 Tariff. One Massachusetts jury after another refused to convict those he had caught smuggling. He wrote very critically of the Puritans, saying that the leaders were “inclined to sedition.” Nevertheless, Randolph believed there were many “who only wait for an opportunity to express their duty to his majesty.” These people were generally “the wealthy persons of all professions” in a society where the “chief professions are merchants ... and wealthy shop-keepers or retailers.”[10] Some of the merchants, particularly recent Anglican immigrants, wanted the yoke of Puritan economic scruples lifted. They were to get their way – but only by Royal fiat.

Upon the revocation of Massachusetts’ charter in 1684, a brief interim council took power, supported by merchants like Richard Wharton. They were mainly interested in using their power to further their business interests. When the crown’s faithful Edmund Andros arrived in 1686, he undid most of what the interim council of merchants had done. His policies turned the Anglican, royalist Richard Wharton against him. Wharton returned to London to lobby for the replacement of Andros. Wharton had been the leader of those agitating for the revocation of the old charter so that Massachusetts Bay could be a Royal colony. As a capitalist, though, he was disappointed in the new political system. Wharton’s loyalty, like most capitalists, was to the dictates of the market.

Edmund Andros (1637-1714)

True Puritans had other reasons to turn against Andros. Andros forced Boston’s South church to host Anglican services. By allowing the services to be protracted, he made the Puritans wait outside their own meeting-house for the Anglicans to finish. Increase Mather was sent to London to lobby against Andros, barely escaping arrest on his way out of the new “Dominion of New England.” That Mather was chosen rather than some merchant or former magistrate shows New England society still spontaneously looked to their ministers for all kinds of leadership. Andros’ “attempt to remodel New England had only served to strengthen popular attachment to the tried and trusted ways of local community life.”[11] Soon loyal New England Puritans expressed their renewed sense of identity. In the same year Andros was overthrown a Boston publisher reprinted the original charter of the Massachusetts Bay Company. Cotton Mather issued a declaration condemning the old regime, calling for the charter to be restored and justifying the seizure “of those few ill men which have been (next to our sins) the grand authors of our miseries.”[12] New England longed to return to the Puritan commonwealth.

The zeal with which Bostonians, backed by Cotton Mather, toppled Edmund Andros and put him in jail shows that Randolph was an overly optimistic Tory. There was still a vibrant Puritan heartland. As Mark A. Peterson argues, first the Restoration and then Andros provoked a renewal of New England Puritanism by renewing its “oppositional mentality.” As threats to their religious principles mounted from outside, Puritans like those of Boston’s Third Church, as well as the Mathers, took the lead in defending traditional Puritan ways.[13] In England, the temper of Puritans had cooled dramatically after the Restoration.[14] After over a half-century of the most remarkable internal stability in the Western world, Andros’ provocation showed that New Englanders had not lost their fire.

Increase Mather in An Earnest Exhortation to the Inhabitants of New England (1676):

It was in respect to some worldly accommodation that other Plantations were erected, but

Religion and not the World was that which our fathers came hither for, Pure Worship and Ordinances without the mixture of human inventions was that which the first fathers of this colony designed in their coming hither. We are the children of the good old non-conformists. . . . And therefore that woeful neglect of the rising generation which hath been amongst us, is a sad sign that we have in great part forgotten our errand in this wilderness; and then why should we marvel that God taketh no pleasure in our young men, but they are numbered for the sword, the present judgment lighting chiefly upon the rising generation.[15]

Increase Mather’s articulate appeal for New England to return to its founding principles strikes at the heart of what economic realities were doing to the second generation of New England Puritans. I believe we should take their jeremiads seriously. Something was draining away from New England. They called what was happening to them “declension.” Piritim Sorokin claimed that when ideational societies begin to break down, prophets call for “fideism.”[16] This may very well be true. Certainly, many of the Puritan observers on the scene were emphatic that declension was setting in. However, there was enough of the old zeal left among enough people to inspire the rise of the jeremiad and create a large audience for the genre in New England. That Increase Mather and many of his contemporaries turned to the jeremiad is a symptom of the vitality of their ideational culture. It’s only when we hear “peace, peace” that there is no peace.

Increase Mather

Commitment to New England’s mission was not a monopoly of the clergy. Though Anglican merchants began to settle there, many of the merchants were Puritan church members in good standing. “So far from being at odds, merchants, magistrates, and ministers through family connections and intermarriage formed one thoroughly interlocked community.”[17] For example, Governor Simon Bradstreet was both a successful merchant and a magistrate; he was the son of a Lincolnshire minister. His son, also Simon, became a minister in New London, and his daughter, Dorothy, married the Rev. Seaborn Cotton. In particular, John Hull, a merchant who became the mint master in Massachusetts, longed for the renewal of Winthrop’s vision of a pure City upon a Hill. He recorded a brief prayer in his diary beseeching God’s forgiveness for his colony for being too lenient on blasphemous Quakers. Peterson particularly chronicles how heavily involved members of Boston’s Third Church were in the upper echelons of commerce. Their wealth came mostly from their active involvement in trade and retailing. They appear to have been “significantly wealthier than their neighbors who were not affiliated with the church.”[18] The picture is very complicated: not all merchants were cosmopolitans agitating for liberalization and not all ministers were purists.

Boston’s Puritans cultivated “an evangelical intensity, an urge to export its culture, that was something new.” — Mark Peterson

Both the Restoration, with its persecution of English Puritanism, and the toleration ushered in by the Glorious Revolution were to have diametrically different effects on English and New England Puritanism. English Puritanism was reduced to mere dissent with the Restoration. Boston was transformed from a backwater of Puritanism into its capital. Through this transformation, Boston’s Puritans cultivated “an evangelical intensity, an urge to export its culture, that was something new.”[19] In addition, in New England, with the Glorious Revolution, hopes for the complete reformation of the Anglican Church were revived.[20] Puritanism’s original purpose was alive and well. Thus, the reflexive defense of a challenged culture at first reinvigorated New England Puritan convictions. At this point, the first generation gets idealized; they focus sharply on their “errand into the wilderness,” and the jeremiad flourishes.

In America, Puritans were not just scattered churches but a distinct province – a province with a strong sense of their own identity since they had been virtually independent.

The apparent return of England to a more Protestant course after the Glorious Revolution and the flight of the Huguenots from France, some of whom came to New England, encouraged a vision of a Protestant union.[21] In response to King William’s Toleration Act of 1689, Cotton Mather moved further and further away from Congregational exclusivism. In England, the Act did what generations of persecution had not been able to do to English nonconformists: in legally granting their right to worship, it took away their cause to fight. With no need for jihad their zeal drained away and their decline was sped. The combination of the people’s rejection of the Puritan state and, about a generation later, legal recognition, was enough to break the back of English Puritanism. Logically, it could have done the same to New England Puritans, for in abolishing religious persecution, the Act also removed what had spurred the first settlers to cross the Atlantic.[22] Distance made the difference. The cause was in England, but the effect was different in America. In America, they were not just scattered churches but a distinct province – a province with a strong sense of their own identity since they had been virtually independent.

Meanwhile, devout New England Puritans had found a new enemy against which to rally the troops. With the memory of Laud’s persecution growing ever fainter, Puritan leaders of the second generation, as shown in their jeremiads, had changed the primary target of their fire: the declension of New England’s own youth. The Pope may still be the anti-Christ, but the anti-Christ could be defeated if only the covenant people were faithful. King Philip’s War (1675-76), the loss of the charter, and economic downturns all served to confirm that God had a controversy with the sinful covenant people. There was always a need for jihad in New England.

John B. Carpenter (Ph.D, ThM, MDiv) is pastor of Covenant Reformed Baptist Church and author of Seven Pillars of a Biblical Church.

[1] Increase Mather, The First Principles of New England (Cambridge, Mass.: Samuel Green, 1673), 3.

[2] Stephen Foster, The Long Argument: English Puritanism and the Shaping of New England Culture, 1570-1700 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991), 199.

[3] Samuel E. Morison, Builders of the Bay Colony (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1930), 164.

[4] Robert Innes, Creating the Commonwealth: The Economic Culture of Puritan New England (New York: W. W. Norton, 1995), 198. Kenneth Silverman, The Life and Times of Cotton Mather (New York: Columbia University Press, 1984), 139.

[5] Mark A. Peterson, The Price of Redemption, 12.

[6] Adam B. Seligman, “Transaction Introduction,” in R. H. Tawney, Religion and the Rise of Capitalism: A Historical Study (London: John Murray, 1926), xxxiv.

[7] Peterson, The Price of Redemption, 11.

[8] Michael G. Hall, The Last American Puritan: the Life of Increase Mather 1639-1723 (Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 1988), xiv.

[9] Innes, Creating the Commonwealth, 199.

[10] Bernard Bailyn, The New England Merchants of the Seventeenth Century (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1955), 155-57.

[11] Richard Johnson, Adjustment to Empire: The New England Colonies, 1675-1717 (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1981), 114.

[12] Massachusetts Bay Colony, A Copy of the King’s Majesty’s Charter for Incorporating the Company of the Massachusetts Bay in New England in America (1689). Cotton Mather, The Declaration of the Gentlemen, Merchants, and Inhabitants of Boston (Boston: Samuel Green, 1689), 4.

[13] Peterson, The Price of Redemption, 174-75.

[14] “It withered in the dark tunnel of persecution between 1660 (Restoration) and 1689

(Toleration).” J. I. Packer, A Quest for Godliness (Wheaton, Ill.: Crossway Books, 1990), 28.

[15] original emphasis, 16-17, according to Bailyn, The New England Merchants of the Seventeenth Century, 140-41.

[16] Michael P. Richard, “Applying Sorokin’s Sociology,” in Sorokin & Civilization: A Centennial Assessment (New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers, 1996), 167.

[17] Stephen Foster, “The Puritan Social Ethic: Class and Calling in the First One Hundred Years of Settlement in New England” (Ph.D. diss., Yale University, 1966), 232.

[18] Peterson, The Price of Redemption, 72.

[19] Peterson, The Price of Redemption, 229, 230.

[20] See Cotton Mather, Eleutheria, or An Idea of the Reformation in England (London: J.R, 1698).

[21] R. Johnson, Adjustment to Empire, 132.

[22] Silverman, The Life and Times of Cotton Mather, 140.